Madeline Wimmer- Fruit Production Extension Educator

This fruit update contains information about…

- Apples- growth stage and thinning; insect & disease management.

- June-bearing strawberries- growth stage, and disease management.

- Additional fruit growth stage highlights.

- “Wild,” non-domesticated fruits in Minnesota.

- Minnesota Department of Agriculture IPM Fruit Update sign up form.

Apples

Growth stage and thinning

Canada thistle:

Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) is a rhizomatous perennial weed that can also spread from “cuttings” or when the plant has been chopped up without removing it from the area. Due to its growth habit and extensive root systems, the plants need to be “exhausted” to fully diminish them. Right now, Canada thistle is getting ready to bloom in many Minnesotan regions, which is a critical management phase because weeds that go to seed (i.e., weed seed rain) can lead to exponentially more weeds in the area. To learn more about managing Canada thistle, check out this previous UMN Fruit and Veg blog post, “A war of attrition: Canada thistle management.”

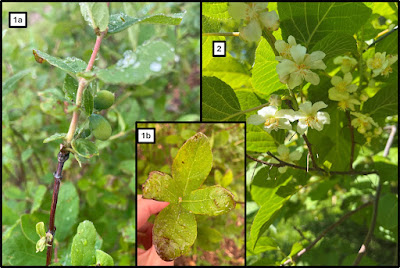

Images: 1a,b) Wild plum (Prunus americana) post fruitset, showing symptoms of plum pocket fungus (Zone 5a, photo taken by Shane Bugeja, UMN Local Extension Educator for Blue Earth County). 2) Blooming black capped raspberries (Rubus ocidentalis) and 3a,b) gooseberries (Ribes uva-crispa) post fruitset, both of which were growing in a small forest stand near Orono, MN (Zone 5a.) 4) Wild grape species (Vitis sp.) in bloom growing downtown in Rochester, MN.

All domesticated, cultivated fruit varieties originate from wild fruits. Some fruit crops are very similar to their wild progenitors, while others steer far away from their original size, sweetness—there’s a reason why strawberries and other fruits were traditionally served sweetened—flavors, or more botanically-relevant properties like having a complete flower. Wild fruits and their foliage are susceptible to diseases, such as the wild plums above, which are showing early symptoms of plum pocket fungus (Taphrina communis). Wild fruit germplasm (e.g., seeds, plant tissues, or genetic sequencing) have been a valuable resource for traditional plant breeding, which can take years to cross and select plants with desirable traits that contribute to a fruit’s eating experience (e.g., fruit sweetness, flavor, color) and ease of management for growers (e.g., disease resistance, cold tolerance, vigor, growth habit.)

If you are interested in subscribing to the MDA IPM Fruit Update series, follow the link below to sign up:

MDA IPM Fruit Update sign up form.

The University of Minnesota Extension fruit production program would like to extend a thank-you to the growers who make these reports possible.

Many apples are at or beyond 16mm in diameter within the southern parts of Minnesota. Just as I mentioned in last week’s update, fruits that have reached these sizes have limited chemical thinning options. Carbaryl and ethephon may still be used with less guaranteed efficacy for growers who missed their thinning opportunity or under-thinned a previous application. Hand thinning is another option, which may be viable for some orchards.

Insect pests

Apple codling moth:

The UMN Horticulture Research Center (HRC) has reported 05/25/24 as their first catch date for apple codling moth and since then, 51 degree day (DD) units have accumulated. The MDA IPM fruit update also reported more incidences of codling moth catches in Wright, Chisago, Rice, Scott, and Washington county.

It is generally recommended that growers apply their first insecticide application to manage codling moths after 250 DD units have accumulated since the first recorded trapping date (i.e., biofix date) . To learn more about effective pesticides and spray programs for apple codling moth management, refer to the Midwest Fruit Pest Management guide.

Note: If insecticide applications are not appearing to control apple codling moth, it may be due to resistance to organophosphates and synthetic pyrethroids; in which case, other insecticide classes should be considered, or alternative control methods such as mating disruption.

Diseases

Apple scab:

Secondary apple scab events continue to be relevant for management in orchards where active lesions are present. As mentioned in last week’s update, primary scab refers to infections resulting from apple scab spores released from overwintering fungal fruiting structures, known as pseudothecium. After all spores have discharged from the overwintering structures, primary scab is considered to be over.

In orchards where primary scab has been forecasted as complete, growers should continue to scout for lesions and apply fungicides for at least two weeks before deciding to reduce fungicide application frequencies. For example, the Cornell NEWA program estimates that the orchard at the UMN Horticulture Research Center finished discharging spores contributing to primary scab on May 21st; thus, the recommendation would be to continue scouting and following a regular program until June 4th. If foliar lesions are present, a routine spray program would continue to be relevant.

Image: June-bearing strawberries showing developing, unripe fruit. Photo taken at Firefly Berries in Rochester, MN (Zone 5a.)

Image: June-bearing strawberries showing developing, unripe fruit. Photo taken at Firefly Berries in Rochester, MN (Zone 5a.)

Growth stage

Insect pests

Apple codling moth:

The UMN Horticulture Research Center (HRC) has reported 05/25/24 as their first catch date for apple codling moth and since then, 51 degree day (DD) units have accumulated. The MDA IPM fruit update also reported more incidences of codling moth catches in Wright, Chisago, Rice, Scott, and Washington county.

It is generally recommended that growers apply their first insecticide application to manage codling moths after 250 DD units have accumulated since the first recorded trapping date (i.e., biofix date) . To learn more about effective pesticides and spray programs for apple codling moth management, refer to the Midwest Fruit Pest Management guide.

Note: If insecticide applications are not appearing to control apple codling moth, it may be due to resistance to organophosphates and synthetic pyrethroids; in which case, other insecticide classes should be considered, or alternative control methods such as mating disruption.

Diseases

Apple scab:

Secondary apple scab events continue to be relevant for management in orchards where active lesions are present. As mentioned in last week’s update, primary scab refers to infections resulting from apple scab spores released from overwintering fungal fruiting structures, known as pseudothecium. After all spores have discharged from the overwintering structures, primary scab is considered to be over.

In orchards where primary scab has been forecasted as complete, growers should continue to scout for lesions and apply fungicides for at least two weeks before deciding to reduce fungicide application frequencies. For example, the Cornell NEWA program estimates that the orchard at the UMN Horticulture Research Center finished discharging spores contributing to primary scab on May 21st; thus, the recommendation would be to continue scouting and following a regular program until June 4th. If foliar lesions are present, a routine spray program would continue to be relevant.

June-bearing strawberries

Growth stage

June-bearing strawberries are steadily producing fruit, but are not at the stage where ripened berries are present.

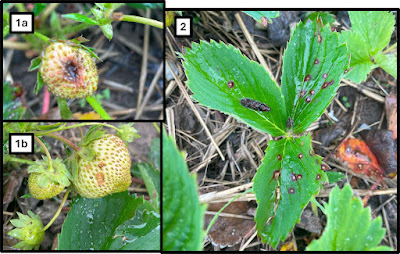

Images: 1a,b) An unripe June-bearing strawberry showing early symptoms of anthracnose fruit rot (Colletotrichum sp.) and 2) June-bearing strawberry leaf showing symptoms of common leaf spot of strawberry (Mycosphaerella fragariae) in SE Minnesota.

Images: 1a,b) An unripe June-bearing strawberry showing early symptoms of anthracnose fruit rot (Colletotrichum sp.) and 2) June-bearing strawberry leaf showing symptoms of common leaf spot of strawberry (Mycosphaerella fragariae) in SE Minnesota.

Diseases

The rainy growing season that many farms are experiencing in Minnesota this year has increased disease pressure, which can be mitigated somewhat for berries that are thoroughly mulched with straw or other organic materials. This week, both foliar and fruit diseases are showing up in SE Minnesota. Common strawberry leaf spot (Mycosphaerella fragariae) was covered in our May 8th fruit update, and this week we’ll focus on what growers should know about anthracnose fruit rot.

Diseases

The rainy growing season that many farms are experiencing in Minnesota this year has increased disease pressure, which can be mitigated somewhat for berries that are thoroughly mulched with straw or other organic materials. This week, both foliar and fruit diseases are showing up in SE Minnesota. Common strawberry leaf spot (Mycosphaerella fragariae) was covered in our May 8th fruit update, and this week we’ll focus on what growers should know about anthracnose fruit rot.

Anthracnose fruit rot:

Also commonly referred to as black spot, anthracnose fruit rot is a disease that can be caused by a few different fungal species including Collectotrichum fragarieae, C. gloeosporioides, and Golmerella cingulata. In addition to fruit rots, these pathogens can lead to crown rot, can affect runners, and lead to leaf petiole infections and bud rot. Fruit lesions start as light brown spots on ripening fruit, which eventually turn dark brown or black and can show signs of pink-to-orange colored masses of spores in lesion centers (refer to images 1a and 1b above).

Also commonly referred to as black spot, anthracnose fruit rot is a disease that can be caused by a few different fungal species including Collectotrichum fragarieae, C. gloeosporioides, and Golmerella cingulata. In addition to fruit rots, these pathogens can lead to crown rot, can affect runners, and lead to leaf petiole infections and bud rot. Fruit lesions start as light brown spots on ripening fruit, which eventually turn dark brown or black and can show signs of pink-to-orange colored masses of spores in lesion centers (refer to images 1a and 1b above).

Managing anthracnose fruit rot can be challenging when environmental conditions are conducive to infection events. Cultural practices, including over fertilizing with nitrogen, can make conditions worse as high soil nitrogen can lead to increases in anthracnose development. Growers who use overhead irrigation may also experience lower disease pressure by switching to drip irrigation.

Images: 1a) Honeyberries/Haskap (Lonicera caerulea), post fruit at Firefly Berries in Rochester Minnesota (Zone 5a) and 1b) honeyberry/haskap leaves showing foliar symptoms on leaf margins. 2) “Female” kiwiberry flowers (Actinidia arguta) with false anthers, in bloom at the UMN HRC (Zone 5a, picture taken by Kate Scapanski, UMN Apple Researcher.)

Images: 1a) Honeyberries/Haskap (Lonicera caerulea), post fruit at Firefly Berries in Rochester Minnesota (Zone 5a) and 1b) honeyberry/haskap leaves showing foliar symptoms on leaf margins. 2) “Female” kiwiberry flowers (Actinidia arguta) with false anthers, in bloom at the UMN HRC (Zone 5a, picture taken by Kate Scapanski, UMN Apple Researcher.)

Additional fruit growth stage highlights

Honeyberries/Haskap

Honeyberries have set fruit and are steadily developing toward ripeness. Likely due to the wet weather conditions this year, some honeyberries in SE MN were showing symptoms of what appears to be a fungal foliar infection. However, resources are limited in regards to identifying honeyberry diseases and, without proper diagnosis protocols, it is challenging to speculate the causal pathogen. Growers have the option to test suspected foliar and other diseases by submitting samples to our UMN plant disease clinic.

Kiwiberries

Kiwiberries, sometimes referred to as hardy kiwis, have been a point of research at the UMN HRC. Growing as a dioecious bine makes kiwiberries a unique crop. Unlike vine crops like grapes, kiwiberry bines do not have tendrils, but instead wrap themselves around structures using their stems. Their dioecious nature means that they bear “male” and “female” flowers on separate plants. Usually one “male” plant is required to pollinate every five or so “female” plants. To learn more about the kiwiberries, visit this UMN webpage, “Minnesota fruit research: Kiwiberries” and “Growing kiwiberry in the home garden,” which has relevant information for commercial growers as well.

Honeyberries have set fruit and are steadily developing toward ripeness. Likely due to the wet weather conditions this year, some honeyberries in SE MN were showing symptoms of what appears to be a fungal foliar infection. However, resources are limited in regards to identifying honeyberry diseases and, without proper diagnosis protocols, it is challenging to speculate the causal pathogen. Growers have the option to test suspected foliar and other diseases by submitting samples to our UMN plant disease clinic.

Kiwiberries

Kiwiberries, sometimes referred to as hardy kiwis, have been a point of research at the UMN HRC. Growing as a dioecious bine makes kiwiberries a unique crop. Unlike vine crops like grapes, kiwiberry bines do not have tendrils, but instead wrap themselves around structures using their stems. Their dioecious nature means that they bear “male” and “female” flowers on separate plants. Usually one “male” plant is required to pollinate every five or so “female” plants. To learn more about the kiwiberries, visit this UMN webpage, “Minnesota fruit research: Kiwiberries” and “Growing kiwiberry in the home garden,” which has relevant information for commercial growers as well.

Blueberries

Image: Early hybrid-blueberry variety with ripening fruits at Blue Fruit Farm, located near Winona, Minnesota (Zone 5a; photo taken by Ben McAvoy.)

Weed management update

Managing weeds can be challenging for perennial fruit growers where tillage and crop rotations are often limited as an option for control. Both annual and perennial weeds can be problematic, especially when they spread and asexually propagate through rhizomes.Canada thistle:

Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) is a rhizomatous perennial weed that can also spread from “cuttings” or when the plant has been chopped up without removing it from the area. Due to its growth habit and extensive root systems, the plants need to be “exhausted” to fully diminish them. Right now, Canada thistle is getting ready to bloom in many Minnesotan regions, which is a critical management phase because weeds that go to seed (i.e., weed seed rain) can lead to exponentially more weeds in the area. To learn more about managing Canada thistle, check out this previous UMN Fruit and Veg blog post, “A war of attrition: Canada thistle management.”

“Wild,” non-domesticated fruits in Minnesota

Images: 1a,b) Wild plum (Prunus americana) post fruitset, showing symptoms of plum pocket fungus (Zone 5a, photo taken by Shane Bugeja, UMN Local Extension Educator for Blue Earth County). 2) Blooming black capped raspberries (Rubus ocidentalis) and 3a,b) gooseberries (Ribes uva-crispa) post fruitset, both of which were growing in a small forest stand near Orono, MN (Zone 5a.) 4) Wild grape species (Vitis sp.) in bloom growing downtown in Rochester, MN.

All domesticated, cultivated fruit varieties originate from wild fruits. Some fruit crops are very similar to their wild progenitors, while others steer far away from their original size, sweetness—there’s a reason why strawberries and other fruits were traditionally served sweetened—flavors, or more botanically-relevant properties like having a complete flower. Wild fruits and their foliage are susceptible to diseases, such as the wild plums above, which are showing early symptoms of plum pocket fungus (Taphrina communis). Wild fruit germplasm (e.g., seeds, plant tissues, or genetic sequencing) have been a valuable resource for traditional plant breeding, which can take years to cross and select plants with desirable traits that contribute to a fruit’s eating experience (e.g., fruit sweetness, flavor, color) and ease of management for growers (e.g., disease resistance, cold tolerance, vigor, growth habit.)

Minnesota Department of Agriculture IPM Fruit Update sign-up form.

For the past two updates, I’ve shared insect pest trap reports from the Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Fruit Updates. For those who are not familiar, the MDA has been keeping reports on insect pest trapping incidences for apples and putting out an IPM newsletter for years. The newsletter complements information presented in the UMN fruit updates and has been valued by many Minnesota fruit growers.If you are interested in subscribing to the MDA IPM Fruit Update series, follow the link below to sign up:

MDA IPM Fruit Update sign up form.

The University of Minnesota Extension fruit production program would like to extend a thank-you to the growers who make these reports possible.

Comments

Post a Comment