As fertilizer and manure prices rise and supply chain shortages persist, you may find yourself buying compost or manure from a different source than usual this year. Or, perhaps you’re relying more heavily on compost or manure than you would have in the past if your go-to amendments are less available or more expensive.

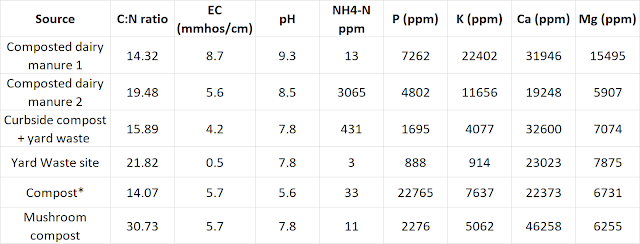

Typically we don’t talk about compost as a nutrient source, but rather as a soil conditioner. This may be a flawed assumption. In December of this year, I was putting together some conference materials related to compost use, and decided to sample six different local sources of compost out of curiosity. The results are listed in the table below.

|

| Compost* was labeled simply as “compost” but in reality contained poultry manure. EC = electrical conductivity (salts) |

Here are some takeaways from my quick study:

Labels are confusing, and sometimes misleading

One of the places I purchased compost from had two options: composted manure, or “compost”. I assumed that the “compost” was vegetative since it was being contrasted with a manure-based option. However, when I prodded a little more, I learned that it actually contained composted poultry manure. It was fully composted, so it wasn’t a food safety concern. However, it still turned out to be significant because it contained 13-25x as much phosphorus as the yard waste composts, and 3-4x as much phosphorus as the composted dairy manures.Compost is not created equally

Even between composts with seemingly similar origins (e.g. composted dairy manure), the nutrient ratios were significantly different between sources. Everything from phosphorus to pH to salts differed substantially from source to source. The carbon to nitrogen ratios were different as well. An important range for carbon to nitrogen ratios is about 25:1 to 30:1. A higher C:N ratio (more carbon rich) will result in microbes tying up (aka immobilizing) plant-available nitrogen. This nitrogen is not necessarily gone, but may not be released in time for the crop to use it. If the C:N ratio is low (more nitrogen rich), the compost breaks down fast and there is plenty of leftover nitrogen for plants to use. However, if this low C:N compost decomposes with no roots to take it up, plant-available nitrogen can be lost from the field. Composted manure is also known to vary quite a bit depending on a wide array of physical and environmental factors.

It’s also worth noting that even if you purchase your compost from the same site each year, it could vary significantly from year to year. For example, if a new type of plant residue is added, the end product will change. Any big changes to an animal’s feed or housing could also lead to a composted manure with a different nutrient content.

Compost can be a significant source of nutrients and salts

Many vegetable farms have excess soil nutrients, and the consequences of this often take a long time to play out. You may have also noticed that all of the composts examined are high in salts. Over time, and especially in high tunnels, we can see the impacts of high salt levels on plant health. Salts drive up the alkalinity of the soil, and in turn the pH, making nutrients less readily available to plants, even if they are present. Applying a lot of compost can also result in very high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen on farms, which can leach through the soil or run off the surface during spring runoff and heavy rainfall events. This has implications for environmental health if these nutrients reach waterways.So how can we deal with this? By testing your compost, you can more carefully apply it based on plant needs, and avoid over-applying certain nutrients like phosphorus or calcium.

How do you test your compost?

The U of MN Soil Testing and Research Analytical Laboratory (STRAL) provides analysis of mature (finished) compost. Finished compost will have a crumbly texture, dark brown color, and a fresh earthy smell indicating decomposition is complete. Unfinished compost is organic matter that is not fully decomposed. If it smells bad, or has a chunky texture, it is probably not finished. The STRAL does not accept unfinished compost samples for analysis.Common analyses include:

- NPK – nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium levels, so you know what you are adding to your soil

- C:N Ratio – carbon to nitrogen ratio indicates how finished the compost is and if nitrogen is more or less readily available to growing plants

- EC – electrical conductance is a measurement of salts in the compost

- pH – a measurement of the alkalinity/acidity of the compost

- Metals – recommended for municipal compost

Please note, the STRAL is not part of the Compost Analysis Proficiency Program through the US Composting Council, nor is it certified by the Minnesota Department of Health for arsenic or heavy metal testing. If contaminants like arsenic are a concern, then testing should be pursued at a certified laboratory.

In addition to testing your compost, make sure you’re testing your soil on a regular basis. This is the best way to track how various nutrients and salts are accumulating in your soil, and the best way to determine future applications of compost, manure, and other sources of fertility.

Author: Natalie Hoidal, Extension educator, local foods and vegetable crops

Contributing author: Shane Bugeja, Extension educator, Blue Earth and Le Sueur Counties

Reviewed by:

Suzanne Frances, Office Manager, Soil Testing and Research Analytical Laboratory, Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station

Angela Gunlogson, Researcher, Soil Testing and Research Analytical Laboratory, Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station

Carl Rosen, Professor, Department of Soil, Water, and Climate, University of Minnesota

Comments

Post a Comment