Madeline Wimmer- UMN Fruit Production Extension Educator

Apples

Growth stage: Fruits between 3.5–5 cm wide

Images: Apple varieties were measuring between 3.5–5 cm at the widest point. Pictured: First Kiss (left, 5 cm), M\cIntosh (middle, 3.5–4 cm), and Honeycrisp (right, 4–5 cm), a variety also known for showing mottled chlorosis on its leaves as seen here. Photos taken at Seekap Orchard in Olmsted County, MN (Zone 5a).

Many apple varieties in SE Minnesota range between 3.5–5 cm measured at their widest point, width-wise. It’s been around six weeks since petal fall occurred in the region. For information related to pest management at this time, refer to the Midwest Fruit Pest Management Guide starting on page 38, “Apple third and summer covers.”

At the University of Minnesota Horticulture Research Center (UMN HRC), it’s been around 835 degree days (baseline 50 F) since the codling moth biofix date occurred on May 15. The Cornell NEWA model estimates this time is close to the beginning of second generation codling moth emergence based on degree day accumulations.

Codling moths (Cydia pomonella) damage apples when adult moths lay their eggs near apple fruitlets. The larvae, which are light pink with a dark head, emerge from the eggs and can cause damage to fruits superficially or internally. When the larva fails to enter the fruit, its attempt can lead to a codling moth “sting,” which leads to superficial damage that can be tolerated for apple seconds, in terms of quality.

However, when the larva is successful in entry, it can begin to feed on the apple and leave frass in its trail, which can lead to entry holes being plugged up with frass. Damage is usually observed within the apple core and developing seeds at this stage. This behavior differentiates codling moths from other moths, or lepidopteran pests like the oriental fruit moth (Grapholita molesta), which tend to move in more random patterns.

After larvae are fully grown, they exit the fruit and generally pupate for 2–3 weeks. After that point, a second generation of moths emerge and can be monitored similarly to the first generation.

References:

Codling moth (California Integrated Pest Management)

Codling moth (Washington State University Extension)

Oriental fruit moth (Washington State University Extension)

It’s been a couple of weeks since the last grape update, which covered bloom. Grapes in southern Minnesota are gaining in size, reaching the E-L growth stage chart stage 29 with berries growing at peppercorn size (around 4mm) or beyond (closer to pea size).

The development phase after fruit set is known as Stage I of development, which is a time where much cell division occurs, leading to an increase in berry size. Berries will continue to be hard and green through Stage II, the lag phase, until they reach Stage III: the ripening phase that starts with veraison (E-L stage 35), where berries begin to soften and gain color.

General pest management recommendations for this time can be found in the Midwest Fruit Pest Management Guide starting on page 166, “Shatter through veraison (color change).”

Basal—or cluster zone—leaf and lateral shoot removal is a simple, low-input practice that removes leaves and lateral shoots from the lower nodes near developing clusters. This can enhance fruit quality by increasing air flow and direct sunlight exposure on developing fruit clusters and basal buds, which give way to shoots and clusters the following growing season. Basal leaf and lateral shoot removal also increases cluster exposure to anything that is sprayed into the canopy (e.g., fungicides).

The timing in which basal leaf removal is completed can make an impact. Research done in the Upper Midwest has shown a positive impact on fruit quality when basal leaf removal is done pre-veraison around E-L stage 29. This is about two weeks post-fruit set when berries are peppercorn in size (1).

This specific stage of basal leaf removal has been shown to cause an increase in total phenolic content for red and white wine grapes, as well as improved wine color stability. Other research has shown decreased titratable acidity and a reduction in vegetative flavors with increased cluster exposure (2) . This is in part due to the increase in berry temperature that occurs with more sunlight exposure.

In-text references

1. Jacob Scharfetter, Beth Ann Workmaster, Amaya Atucha. Preveraison Leaf Removal Changes Fruit Zone Microclimate and Phenolics in Cold Climate Interspecific Hybrid Grapes Grown under Cool Climate Conditions. Am J Enol Vitic. 2019 70:297-307 ; DOI: 10.5344/ajev.2019.18052

2. Jean Riesterer-Loper, Beth Ann Workmaster, Amaya Atucha.Restricted accessImpact of Fruit Zone Sunlight Exposure on Ripening Profiles of Cold Climate Interspecific Hybrid Winegrapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 2019 70:286-296 ; DOI: 10.5344/ajev.2019.18080

Most honeyberry (haskap, edible honeysuckle) varieties have reached peak ripeness and are reaching the end of their harvest window in growing regions throughout the lower half of Minnesota. After honeyberries first turn blue, they tend to need a couple of weeks until they reach peak ripeness.

Growers can use a combination of taste along with a refractometer to track ripeness and flavor development. The final brix level goal for harvest is usually 15 brix or higher, as recommended by Montana Extension honeyberry breeder Zach Miller. Similar to other fruit crops, there are times when environmental conditions (e.g., high winds) or other pressures will require earlier harvest.

This past week, the first Upper Midwest Honeyberry Academy was hosted at Haskap Minnesota near Stillwater by the University of Minnesota Extension and University of Wisconsin Extension. This was a great opportunity to learn about honeyberries from University of Saskatchewan Emeritus Professor Bob Bohrs and Montana State Extension Professor Zach Miller, who both have contributed to breeding and researching honeyberries.

For those who were unable to attend, stay tuned for an article that summarizes the event in UMN Fruit and Veg News.

Resources on raspberry cane diseases:

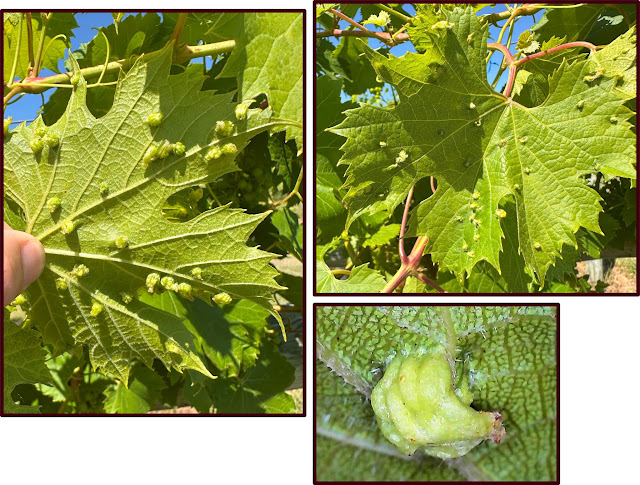

Images: Phylloxera (Dactylosphaera vitifoliae) is an insect pest of grapes that can cause galls on the leaves. The number of galls on the leaf in the above photos shows mild impact. This number of galls is typical for first generation phylloxera gall production, with sequential generations producing more.

Images: Phylloxera (Dactylosphaera vitifoliae) is an insect pest of grapes that can cause galls on the leaves. The number of galls on the leaf in the above photos shows mild impact. This number of galls is typical for first generation phylloxera gall production, with sequential generations producing more.

Resources on phylloxera:

Apples

- Growth stage: Fruits between 3.5–5 cm wide

- Pest highlight: Identifying codling moth symptoms

- Growth stage: Berries ranging from peppercorn to pea size

- Optimal timing for basal leaf and lateral shoot removal

- Growth stage: Nearing end of harvest

- Stay tuned: 2025 Upper Midwest Honeyberry Academy Recap

- Raspberry spur blight on primocanes

- Phylloxera leaf galls

Apples

Growth stage: Fruits between 3.5–5 cm wide

Images: Apple varieties were measuring between 3.5–5 cm at the widest point. Pictured: First Kiss (left, 5 cm), M\cIntosh (middle, 3.5–4 cm), and Honeycrisp (right, 4–5 cm), a variety also known for showing mottled chlorosis on its leaves as seen here. Photos taken at Seekap Orchard in Olmsted County, MN (Zone 5a). Many apple varieties in SE Minnesota range between 3.5–5 cm measured at their widest point, width-wise. It’s been around six weeks since petal fall occurred in the region. For information related to pest management at this time, refer to the Midwest Fruit Pest Management Guide starting on page 38, “Apple third and summer covers.”

At the University of Minnesota Horticulture Research Center (UMN HRC), it’s been around 835 degree days (baseline 50 F) since the codling moth biofix date occurred on May 15. The Cornell NEWA model estimates this time is close to the beginning of second generation codling moth emergence based on degree day accumulations.

Pest highlight: Identifying codling moth symptoms: Internal feeding

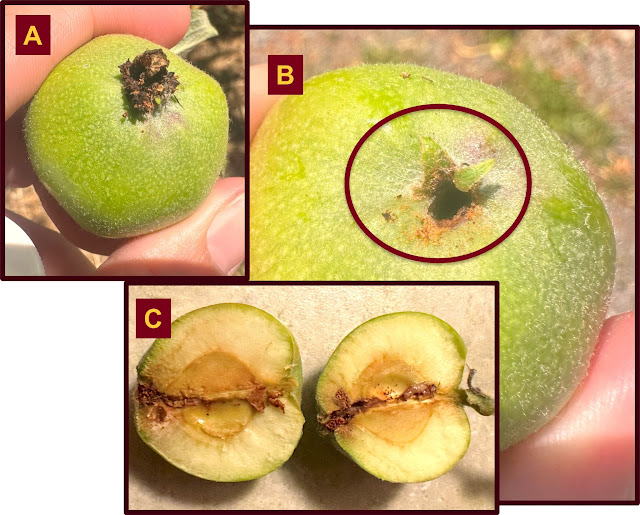

Images: An Gravenstein variety apple showing signs of damage classic to codling moth (Cydia pomonella). A: frass at the apple calyx end is characteristic of codling moth larvae. B: when the frass is removed, an entry hole is revealed. C: the apple damage was localized to the apple core. Photos taken during a trip in Sonoma County, California (Zone 9b).

Codling moths (Cydia pomonella) damage apples when adult moths lay their eggs near apple fruitlets. The larvae, which are light pink with a dark head, emerge from the eggs and can cause damage to fruits superficially or internally. When the larva fails to enter the fruit, its attempt can lead to a codling moth “sting,” which leads to superficial damage that can be tolerated for apple seconds, in terms of quality.

However, when the larva is successful in entry, it can begin to feed on the apple and leave frass in its trail, which can lead to entry holes being plugged up with frass. Damage is usually observed within the apple core and developing seeds at this stage. This behavior differentiates codling moths from other moths, or lepidopteran pests like the oriental fruit moth (Grapholita molesta), which tend to move in more random patterns.

After larvae are fully grown, they exit the fruit and generally pupate for 2–3 weeks. After that point, a second generation of moths emerge and can be monitored similarly to the first generation.

References:

Codling moth (California Integrated Pest Management)

Codling moth (Washington State University Extension)

Oriental fruit moth (Washington State University Extension)

Grapes

Growth stage: Berries ranging from peppercorn to pea size

Images: Brianna (left), Marquette (middle), and Itasca (right) are continuing to develop during this initial ripening phase known as Phase I where cell division occurs and the berries increase in size. The Marquette grapes also show what is sometimes called, “hens and chicks” where some berries are lagged in development.

It’s been a couple of weeks since the last grape update, which covered bloom. Grapes in southern Minnesota are gaining in size, reaching the E-L growth stage chart stage 29 with berries growing at peppercorn size (around 4mm) or beyond (closer to pea size).

The development phase after fruit set is known as Stage I of development, which is a time where much cell division occurs, leading to an increase in berry size. Berries will continue to be hard and green through Stage II, the lag phase, until they reach Stage III: the ripening phase that starts with veraison (E-L stage 35), where berries begin to soften and gain color.

General pest management recommendations for this time can be found in the Midwest Fruit Pest Management Guide starting on page 166, “Shatter through veraison (color change).”

Optimal timing for basal leaf and lateral shoot removal

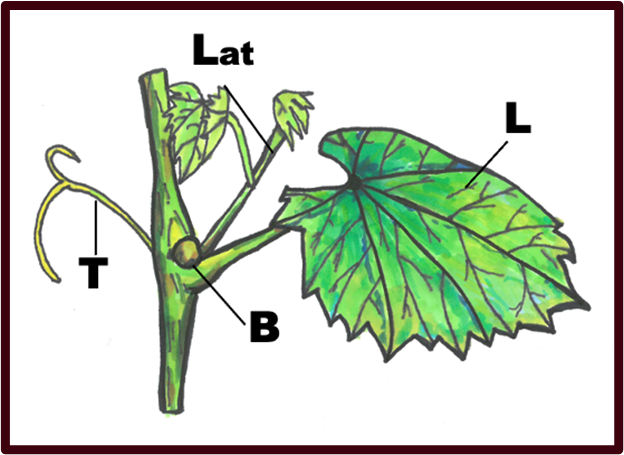

Image: A grape shoot node, or region with developing bud (B), lateral shoot (Lat), leaf (L), and tendril (T). Illustration by Madeline Wimmer.

Basal—or cluster zone—leaf and lateral shoot removal is a simple, low-input practice that removes leaves and lateral shoots from the lower nodes near developing clusters. This can enhance fruit quality by increasing air flow and direct sunlight exposure on developing fruit clusters and basal buds, which give way to shoots and clusters the following growing season. Basal leaf and lateral shoot removal also increases cluster exposure to anything that is sprayed into the canopy (e.g., fungicides).

The timing in which basal leaf removal is completed can make an impact. Research done in the Upper Midwest has shown a positive impact on fruit quality when basal leaf removal is done pre-veraison around E-L stage 29. This is about two weeks post-fruit set when berries are peppercorn in size (1).

This specific stage of basal leaf removal has been shown to cause an increase in total phenolic content for red and white wine grapes, as well as improved wine color stability. Other research has shown decreased titratable acidity and a reduction in vegetative flavors with increased cluster exposure (2) . This is in part due to the increase in berry temperature that occurs with more sunlight exposure.

Best practices:

Basal leaf removal

- Basal leaf and lateral shoot removal involves removing 1-3 leaves per shoot in the cluster zone and taking out any lateral shoots growing from the first three node positions.

- The number of basal leaves removed depends on which direction a vineyard row side is oriented, how much canopy length each vine has, and the general vigor of the vines.

- Grapevines planted in rows that run east to west have a north and south side facing canopy. In this situation it is often best to remove more leaves on the canopy northside where less intense sun exposure occurs.

- Vineyard rows that run north to south have canopies with east and west side exposure and can have a similar number of leaves removed from each canopy side.

Basal lateral shoot removal

- For high-vigor vineyards experiencing extensive basal lateral shoot growth, removal when shoots are first emerging can be a quick way to address the issue. For VSP vines grown with catchwires, lateral shoots can sometimes be tucked into the catchwire “basket”, but this can still limit airflow in already-dense canopies.

In-text references

1. Jacob Scharfetter, Beth Ann Workmaster, Amaya Atucha. Preveraison Leaf Removal Changes Fruit Zone Microclimate and Phenolics in Cold Climate Interspecific Hybrid Grapes Grown under Cool Climate Conditions. Am J Enol Vitic. 2019 70:297-307 ; DOI: 10.5344/ajev.2019.18052

2. Jean Riesterer-Loper, Beth Ann Workmaster, Amaya Atucha.Restricted accessImpact of Fruit Zone Sunlight Exposure on Ripening Profiles of Cold Climate Interspecific Hybrid Winegrapes. Am J Enol Vitic. 2019 70:286-296 ; DOI: 10.5344/ajev.2019.18080

Honeyberries

Growth stage: End of harvest

Images: Honeyberries, sometimes called Haskap, are a blue fruit that grows on a shrub. The berries tend to ripen in mid-to-late June in many Minnesota regions.

Most honeyberry (haskap, edible honeysuckle) varieties have reached peak ripeness and are reaching the end of their harvest window in growing regions throughout the lower half of Minnesota. After honeyberries first turn blue, they tend to need a couple of weeks until they reach peak ripeness.

Growers can use a combination of taste along with a refractometer to track ripeness and flavor development. The final brix level goal for harvest is usually 15 brix or higher, as recommended by Montana Extension honeyberry breeder Zach Miller. Similar to other fruit crops, there are times when environmental conditions (e.g., high winds) or other pressures will require earlier harvest.

Stay tuned: 2025 Upper Midwest Honeyberry Academy Recap

This past week, the first Upper Midwest Honeyberry Academy was hosted at Haskap Minnesota near Stillwater by the University of Minnesota Extension and University of Wisconsin Extension. This was a great opportunity to learn about honeyberries from University of Saskatchewan Emeritus Professor Bob Bohrs and Montana State Extension Professor Zach Miller, who both have contributed to breeding and researching honeyberries.

For those who were unable to attend, stay tuned for an article that summarizes the event in UMN Fruit and Veg News.

Zooming in

Raspberry spur blight on primocanes

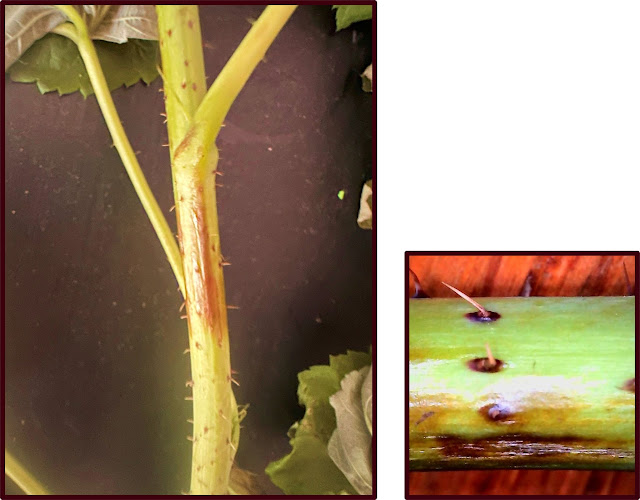

Images: A photo of a summer-bearing raspberry primocane (i.e., current season’s growth) with developing lesions on the main stem and leaf petiole, which may be symptoms of spur blight (diagnosis not confirmed).

Resources on raspberry cane diseases:

- Raspberry cane diseases (UMN Extension)

- 06/12/25 Update on diseased canes (UMN Extension, Fruit and Veg News)

- 05/07/25 Raspberry cane diseases (UMN Extension, Fruit and Veg News)

Phylloxera galls on grape leaf

Resources on phylloxera:

- Practical tips for managing phylloxera in Minnesota (University of Minnesota)

- Grape phylloxera (University of Minnesota, Fruit and Veg News)Watch for phylloxera leaf galls (University of Wisconsin, Madison)

Thank you to our farm and ag professional partners for contributions to the UMN Fruit Update series. Unless otherwise credited, photos were taken by Madeline Wimmer or sourced from the UMN Extension system.

This article may be shared for educational purposes with attribution to the University of Minnesota Extension. For other uses, please contact UMN Extension for permission.

This article may be shared for educational purposes with attribution to the University of Minnesota Extension. For other uses, please contact UMN Extension for permission.

Comments

Post a Comment