Madeline Wimmer- UMN Fruit Production Extension Educator

This fruit update contains information about…

Bird management in vineyards is an expensive and time consuming process that is necessary to maintain a full harvest. Bird pressure changes depending on a vineyard’s location and how close it is to a forest edge. Other variations that contribute to bird pressure include seasonal trends and weather conditions, which grape varieties are being grown, and which species of birds are present (i.e., not all bird species eat grapes). There are a number of different methods to keep birds from damaging grape clusters, many of which can be installed around veraison or closer to harvest time.

Bird netting

Using nets as a physical barrier to block birds from reaching fruit clusters is still considered the most effective and reliable way to prevent bird damage. The most common mesh sizes for bird netting range from ½-¾ of an inch, which is much larger than the hail netting recommended for hail and insect exclusion in apples. Some netting types are more rigid than others. Black plastic netting tends to be more rigid, while white or green knit drape netting is usually more flexible. The type of netting material used and the netting width changes how it is applied and how it can be stored. Before applying bird netting, growers should aim to finish any canopy management needed, such as hedging or skirting.

Note: No matter which type of netting you choose to install, remember to wear buttonless shirts during its installation, which can be a frustrating experience as netting holes can frequently catch buttons.

Plastic mesh netting

Depending on its width, black plastic netting can either be installed over the top of a canopy and clipped underneath the vines, or applied as two separate half nets, one for each row side. Because of how rigid this type of netting is, it does not bunch well and is usually wound up for storage. For vineyards that have rows with different lengths, organizing this type of netting with clear labels indicating net/row lengths will save time when installing netting the following year.

Knit drape netting

Knit drape netting is usually made from yarn or high density polyethylene. It tends to bunch much easier than plastic mesh netting. This allows for it to be stored in bunches and applied with netting mechanisms like a Netter Getter, or home made options that pipe the netting through a tube, after which point the netting is stretched over the top of vineyard rows and clipped underneath the vines to keep it in place.

Additional bird deterrent options

A number of innovative options have been developed to deter birds as an alternative to netting. These include bird distress calls, predator recordings, and cannons, which all use sounds to alarm and confuse birds. Additionally, visual deterrents—often shiny, or mimicking the appearance of predatory birds—also exist and can be hung up around the vineyard to scare birds. These techniques require much less labor to install, and can be moderately effective at deterring birds, especially when bird pressure is low for a given vineyard; however, birds can eventually acclimate to some of these methods, making them less effective over time. Finally, the most recent technology that has been adopted in vineyards for bird deterrence are lasers, sometimes referred to as “laser scarecrows,” as well as drone technology.

Additional reading:

Comparing bird management tactics for vineyards and berry crops (University of Minnesota Extension publication)

UMN Extension received a photo submission recently from a grower who had sooty mold (Capnodium sp. and others) coating a portion of their grape leaves and on the surrounding clusters. The fungal pathogens that cause sooty mold live on plant surfaces and feed on the high sugar waste excretions (also known as honeydew) from piercing and sucking insect pests. Aphids, whiteflies, mealybugs, and soft scales all can be associated with sooty mold and honeydew. Thankfully these pests are not a common or serious issue for cold climate grape production. Exactly what caused the sooty mold in these pictures is hard to ID confidently. However, the fuzzy white blobs in the background could be a species of scale insect.

About grapevine scale pests

There are a few different scales that affect grapes, including the grape scale (Diaspidiotus uvae)—which is related to the San Jose scale that affects fruit trees—and the wooly vine scale (Pulvinaria vitis), also referred to as the grape-cottony maple scale. True to their name, wooly vine scales’ egg sacs appear to be made of fabric, and can be surprising to see in the field. In contrast, the grape scale can be difficult to notice because it nestles itself under grapevine bark.

For small scale growers (no pun intended), grape scale species and their egg sacs should be physically removed to prevent further damage to vines. Chemical management for soft scales is usually timed to target the crawler stage, which usually coincides with vineyard pre-bloom sprays, however, some strategies can target scales during dormancy as well. Refer to the Midwest Fruit Pest Management Guide starting on page 154 to learn more about chemical management options for soft scales.

Thank you to local educators Shane Bugeja, UMN Local Extension Educator for his knowledge contributions to this section.

The University of Minnesota wants to hear from grape growers to find out how many vineyards face damage from the disease black rot, caused by the pathogen (Guignardia bidwellii).

About black rot:

Black rot shows up as foliar symptoms on grape leaves, and it can negatively impact grape yields when clusters are infected. Symptoms on grapes start as circular, dark lesions that eventually take over whole grape berries, which initially appear as a soft rot, and eventually berries desiccate, or dry up. Following a general fungicide program can help prevent black rot outbreaks, but in years with frequent rain occurrences like we’ve had this year, long lasting spray coverage can be challenging, and outbreaks are more likely to occur.

Take our 2 minute survey:

Whether you think you’ve seen black rot, aren’t sure, or haven’t witnessed it, taking this short survey will help us know how prevalent it is in Minnesota and surrounding areas.

University of Minnesota Black Rot Survey

Summercrisp is one of three cold-hardy pear varieties released from the University of Minnesota. An earlier UMN document, “Summercrisp Pear” mentions that its original introduction to the UMN Horticulture Research Center was in 1933 by John Gaspard of Caledonia, Minnesota, and the parentage for Summercrisp is still unknown to this day. Summercrisp trees are hardy up to USDA hardiness zone 4. They can reach as tall as 12-20 feet tall with canopies that can grow as large as 20 feet wide.

Summercrisp pears are best harvested when the fruit is slightly under ripe with a crispy-to-slight-crunch texture and a modest amount of color. Recommendations for optimal post-harvest handling for Summercrisp pears includes refrigeration shortly after harvesting to uphold its texture and prevent it from ripening off the tree. Culinary uses for Summercrisp include preparation by grilling or searing slices, and/or adding it as an addition to a summer salad, using it for baked goods, or simply enjoyed as it is in its original fresh state.

This fruit update contains information about…

- Apples

- Apple curculio

- Grapes

- Bird netting and additional bird deterrents

- Sooty mold and scales on grapevines

- Black rot grape growers survey

- Pears

- Summercrisp harvest updates

Apples

Apple curculio

This week’s section on the apple curculio, “Apple curculio: A lesser-known orchard pest” is posted as a separate article in our Fruit and Veg Newsletter. Many growers are familiar with the plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar), but in this article, we explore what is known about apple curculios (Anthonomus quadrigibbus), including their identification, lifecycle, and potential management strategies.Grapes

Bird netting and additional bird deterrents

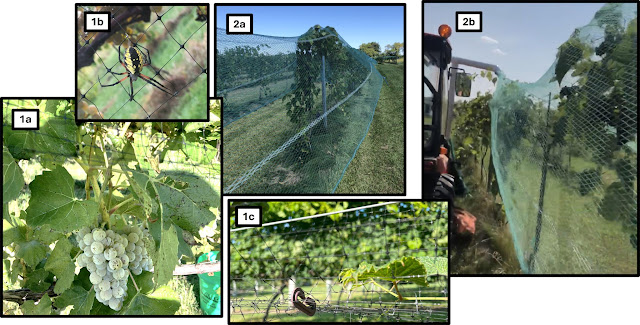

Images: 1a) Rigid, plastic mesh netting with 3/4in mesh demonstrating how netting can be lifted and temporarily clipped above clusters to make harvesting easier; b) close up showing a yellow garden spider for size comparison; c) netting clips can fasten any type of net and can be clipped below grapevines. 2a) An alternative over-the-row knit mesh netting is more flexible, can be applied mechanically (2b), and can additionally be clipped underneath vines to keep it in place.

Bird management in vineyards is an expensive and time consuming process that is necessary to maintain a full harvest. Bird pressure changes depending on a vineyard’s location and how close it is to a forest edge. Other variations that contribute to bird pressure include seasonal trends and weather conditions, which grape varieties are being grown, and which species of birds are present (i.e., not all bird species eat grapes). There are a number of different methods to keep birds from damaging grape clusters, many of which can be installed around veraison or closer to harvest time.

Bird netting

Using nets as a physical barrier to block birds from reaching fruit clusters is still considered the most effective and reliable way to prevent bird damage. The most common mesh sizes for bird netting range from ½-¾ of an inch, which is much larger than the hail netting recommended for hail and insect exclusion in apples. Some netting types are more rigid than others. Black plastic netting tends to be more rigid, while white or green knit drape netting is usually more flexible. The type of netting material used and the netting width changes how it is applied and how it can be stored. Before applying bird netting, growers should aim to finish any canopy management needed, such as hedging or skirting.

Note: No matter which type of netting you choose to install, remember to wear buttonless shirts during its installation, which can be a frustrating experience as netting holes can frequently catch buttons.

Plastic mesh netting

Image: Black plastic netting is best stored as a spool. In this vineyard, the netting was clipped to pvc tubing and rolled up using either a forklift or attached rebar and a handmade crank fit to the pvc tube. Photo taken at Cambridge Winery located in Cambridge, Wisconsin (Zone 5b).

Depending on its width, black plastic netting can either be installed over the top of a canopy and clipped underneath the vines, or applied as two separate half nets, one for each row side. Because of how rigid this type of netting is, it does not bunch well and is usually wound up for storage. For vineyards that have rows with different lengths, organizing this type of netting with clear labels indicating net/row lengths will save time when installing netting the following year.

Knit drape netting

Knit drape netting is usually made from yarn or high density polyethylene. It tends to bunch much easier than plastic mesh netting. This allows for it to be stored in bunches and applied with netting mechanisms like a Netter Getter, or home made options that pipe the netting through a tube, after which point the netting is stretched over the top of vineyard rows and clipped underneath the vines to keep it in place.

Additional bird deterrent options

A number of innovative options have been developed to deter birds as an alternative to netting. These include bird distress calls, predator recordings, and cannons, which all use sounds to alarm and confuse birds. Additionally, visual deterrents—often shiny, or mimicking the appearance of predatory birds—also exist and can be hung up around the vineyard to scare birds. These techniques require much less labor to install, and can be moderately effective at deterring birds, especially when bird pressure is low for a given vineyard; however, birds can eventually acclimate to some of these methods, making them less effective over time. Finally, the most recent technology that has been adopted in vineyards for bird deterrence are lasers, sometimes referred to as “laser scarecrows,” as well as drone technology.

Additional reading:

Comparing bird management tactics for vineyards and berry crops (University of Minnesota Extension publication)

Sooty mold and scales on grapevines

Image: 1) The dark blotches on these grape leaves and fruit results from a fungus feeding on honeydew: a sweet substance secreted by aphids, whiteflies, mealybugs, and soft scales. In this case, the excretions were likely caused by scale as evidenced by what appeared to be scale egg sacks (2). Sooty mold does not directly harm grapes, but can impact photosynthesis. Photos submitted by a grower from Meeker County, MN (Zone 4b).

UMN Extension received a photo submission recently from a grower who had sooty mold (Capnodium sp. and others) coating a portion of their grape leaves and on the surrounding clusters. The fungal pathogens that cause sooty mold live on plant surfaces and feed on the high sugar waste excretions (also known as honeydew) from piercing and sucking insect pests. Aphids, whiteflies, mealybugs, and soft scales all can be associated with sooty mold and honeydew. Thankfully these pests are not a common or serious issue for cold climate grape production. Exactly what caused the sooty mold in these pictures is hard to ID confidently. However, the fuzzy white blobs in the background could be a species of scale insect.

About grapevine scale pests

Images: The wooly vine scale female adults (left image) creates a cotton-like egg sac on the outside of grapevine canes and other woody parts. This magnolia scale (right image; Neolecanium cornuparvum) is exuding honeydew: a sweet sticky substance that becomes a source of food for the fungi that cause sooty mold; photo taken by Shane Bugeja, UMN Local Extension Educator.

There are a few different scales that affect grapes, including the grape scale (Diaspidiotus uvae)—which is related to the San Jose scale that affects fruit trees—and the wooly vine scale (Pulvinaria vitis), also referred to as the grape-cottony maple scale. True to their name, wooly vine scales’ egg sacs appear to be made of fabric, and can be surprising to see in the field. In contrast, the grape scale can be difficult to notice because it nestles itself under grapevine bark.

For small scale growers (no pun intended), grape scale species and their egg sacs should be physically removed to prevent further damage to vines. Chemical management for soft scales is usually timed to target the crawler stage, which usually coincides with vineyard pre-bloom sprays, however, some strategies can target scales during dormancy as well. Refer to the Midwest Fruit Pest Management Guide starting on page 154 to learn more about chemical management options for soft scales.

Thank you to local educators Shane Bugeja, UMN Local Extension Educator for his knowledge contributions to this section.

Black rot grower survey

Images: Black rot is a disease caused by the fungal pathogen Guignardia bidwellii, and can affect grape leaves (left image), but is most devastating when it infects grape clusters (right image).

The University of Minnesota wants to hear from grape growers to find out how many vineyards face damage from the disease black rot, caused by the pathogen (Guignardia bidwellii).

About black rot:

Black rot shows up as foliar symptoms on grape leaves, and it can negatively impact grape yields when clusters are infected. Symptoms on grapes start as circular, dark lesions that eventually take over whole grape berries, which initially appear as a soft rot, and eventually berries desiccate, or dry up. Following a general fungicide program can help prevent black rot outbreaks, but in years with frequent rain occurrences like we’ve had this year, long lasting spray coverage can be challenging, and outbreaks are more likely to occur.

Take our 2 minute survey:

Whether you think you’ve seen black rot, aren’t sure, or haven’t witnessed it, taking this short survey will help us know how prevalent it is in Minnesota and surrounding areas.

University of Minnesota Black Rot Survey

Pears

Summercrisp

Image: The University of Minnesota recommends harvesting Summercrisp pear before they are fully ripened, when they are crisp and slightly blushed with color. Photo taken at Maplebrook Farm of Olmsted County, Minnesota (Zone 5a).

Summercrisp is one of three cold-hardy pear varieties released from the University of Minnesota. An earlier UMN document, “Summercrisp Pear” mentions that its original introduction to the UMN Horticulture Research Center was in 1933 by John Gaspard of Caledonia, Minnesota, and the parentage for Summercrisp is still unknown to this day. Summercrisp trees are hardy up to USDA hardiness zone 4. They can reach as tall as 12-20 feet tall with canopies that can grow as large as 20 feet wide.

Summercrisp pears are best harvested when the fruit is slightly under ripe with a crispy-to-slight-crunch texture and a modest amount of color. Recommendations for optimal post-harvest handling for Summercrisp pears includes refrigeration shortly after harvesting to uphold its texture and prevent it from ripening off the tree. Culinary uses for Summercrisp include preparation by grilling or searing slices, and/or adding it as an addition to a summer salad, using it for baked goods, or simply enjoyed as it is in its original fresh state.

❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖❖

The University of Minnesota Extension fruit production program would like to extend a thank-you to our fruit grower partners who make these reports possible.

Non-credited photos in these publications were taken by the author, Madeline Kay Wimmer, M.S.

The University of Minnesota Extension fruit production program would like to extend a thank-you to our fruit grower partners who make these reports possible.

Non-credited photos in these publications were taken by the author, Madeline Kay Wimmer, M.S.

Comments

Post a Comment