|

| A renewal cane of a mature vine that did not produce live buds. Photo: Annie Klodd. |

Author: Annie Klodd, University of Minnesota Extension Educator

While the majority of grape growers in Minnesota and Wisconsin reported no freeze damage to their vineyards during our May 13th webinar, several grape growers have called me to report vines that failed to break bud. In most cases I know of, the dead buds occurred on either newly planted vines, or new canes on mature vines that were trained up to replace dead cordons.

More bud death has occurred on the outer portion of the canes, while the buds toward the base of the canes had better rates of survival. This is to be expected, and is also one of the reasons we stress the importance of cutting back renewal canes to 15 inches rather than trying to renew the whole cordon at once. In all cases, the canes themselves are healthy and only the buds are dead.

|

| Buds that froze during bud swell. Photo: Annie Klodd |

In some cases, it is clear that the damage was due to the mid-May freeze event, because the buds swelled before dying (see photo below). However in many cases, the buds did not swell at all and are completely dead. In these instances, it becomes more complicated to assign an exact cause to the bud injury.

These events call for a review of how bud injury happens. I will discuss this in the context of the weather events we experienced in the past year.

Early Cold Snaps in the Fall

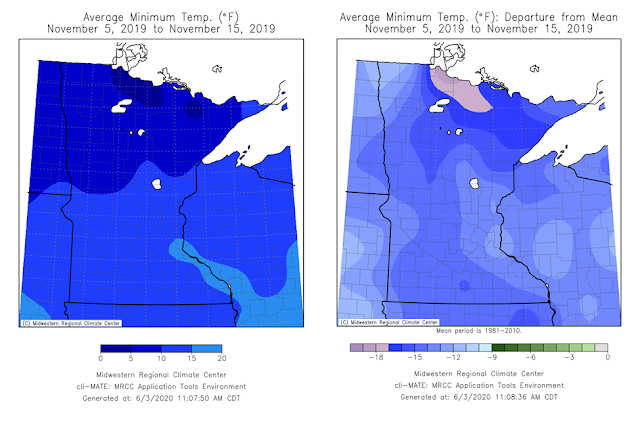

During the first half of November, the upper Midwest experienced low temperatures well below the average lows for that time of the year (see two maps below). During this time, the vines were not fully acclimated to winter temperatures yet, and were still trying to harden off for the winter. This hardening off process involves a physiological process inside the vines that prepares the buds for dormancy. Early cold snaps that hit the vines before they are hardened off (prepared for winter) can cause bud damage.

If the vines have buds that did not swell at all, this cold event may have been the cause.

|

| Average minimum temperatures between November 5-15, 2019 (left), and departure from the 30-year average (right). |

These early fall freeze events reached beyond the upper Midwest. For example, Zach Miller, Professor of Horticulture at Montana State University, reported nighttime temperatures between 18-25 degrees in late September, 2019. By October, temperatures were in the teens. Damage was not as severe as some growers expected, but Petite Pearl, a popular variety in Montana, was heavily impacted and overall bud injury was more common further down on the cordons and canes.

Cool, wet 2019 growing season

In a cool and wet growing season such as 2019, new vines, suckers and renewal canes have fewer growing degree days in which to grow and harden off for winter. In other words, grapevines require a certain amount of heat accumulation over the season to grow, develop, and senesce. If more of our days are cooler, then there is less heat accumulation than if the average temperatures were warmer over the season.

|

| A one-year old vine with dead buds, which must be re-trained from suckers. Photo: Annie Klodd |

This can present a challenge for new vines and canes, which require time and heat to establish and develop energy storage for the winter. Shorter or cooler seasons may lead to poor establishment and poor bud development for the following season. If the vines are already unhealthy, such as if they were severely damaged by the 2019 polar vortex, they may have an even harder time growing and hardening off new canes.

If new vines were planted later, such as after June 1, their season is shortened further and they have less time to grow and harden off before winter, increasing their risk of winter injury (see photo above).

Different weather factors interact can also create accumulated effects on the vines, such that a cool wet season followed by a November cold snap may have led to enhanced damage to bud health.

May Frost and Freeze Event

As stated at the beginning of this article, the vast majority of growers who attended our May 13 webinar reported that they did not experience frost or freeze damage from the cold event between May 8-12. For the most part, grapevines in Minnesota were still in early or late bud swell, and temperatures did not get low enough in most areas to impact buds at that stage.

However, microclimate effects can cause some vineyards to experience damage that surrounding areas did not. For example, cold valley bottoms can cause the temperatures to fall well below the surrounding area. Warmer microclimates can cause vines to speed ahead in bud break and therefore be more vulnerable to late frost events. A handful of growers reported moderate or severe frost damage to buds in late bud swell at that time. If the damaged buds appear to have swelled before turning brown and soft, the damage is likely to have been caused by a late spring freeze event.

Late winter (dormant) cold snap

A rarer cause of bud injury is a cold snap occurring after temperatures begin to warm in the late winter during dormancy. Grapevines are at their peak levels of cold-hardiness in December and January. Then, above-freezing temperatures in February and March cause the vines to slowly start exiting dormancy, which is visible to us via sap flow from pruning cuts. As temperatures gradually rise, the vines gradually de-acclimate to the winter; in other words the buds are slowly losing their hardiness even while dormant. This is necessary in order for the buds to break in spring.

The rate of de-acclimation, or how hardy the buds are at each point in time, is not well known in the cold hardy hybrid varieties. However, the reason it is more rare for this to cause bud injury relative to a fall cold snap, is that even though the buds are slowly losing their hardiness in early spring, it still requires very cold temperatures to kill dormant buds on cold hardy hybrid vines. They are more sensitive to rapid temperatures fluctuations in the fall before dormancy, as described above.

Coping with Poor Bud Break on Grapevines

Mature grapevines with renewal canes: Many of the growers I spoke to were having issues with mature vines that they had been retraining from severe die-back in 2019. Mature grapevines with poor bud break on the renewal canes should either be trained up again from new canes from suckers, and/or plan to use one of the healthy new shoots from further back on the cane to continue developing the cordon this season. Keep in mind that it is common for canes and buds to become weaker further out on the length of the cane, and do not attempt to lay down the full length of the canes for new cordons while pruning next winter.

One-year old grapevines: If one-year old grapevines failed to break bud, cut into a few canes and see if they are healthy (green). Consider digging up a couple of the vines, cutting into roots, and checking if the tissue inside is healthy (creamy-white and firm). If the wood and roots are healthy, they are likely to push up suckers that can be used to re-train the vine. As the roots have more energy than they did upon planting, the suckers should grow up faster than last year and harden off properly.

Replacing varieties or relocating vineyards

There is no simple silver bullet solution to bud injury on grapevines. We cannot make dead buds come back to life, so I understand that the solutions I am suggesting here are not easy.

With that said, if the vineyard is planted in a valley or otherwise wet, cool area then the same problems are likely to continue occurring. This is especially true as our climate trends toward more rain and less predictable temperatures.

Depending on your situation, you may consider relocating the vineyard to a better area, or abandoning a particularly unsuitable section of the field and planting somewhere else. Many vineyards go through this at some point; it is hard, but can be the best solution. If it is necessary to have vines planted in a poor site, such as if it is adjacent to the winery building and the vines are needed for aesthetics, or if you simply live in a colder part of the state, considering trying another variety with better cold hardiness.

Author: Annie Klodd, Extension Educator-Fruit and Vegetable Production

With input from John and Jenny Thull, University of Minnesota Horticulture and Dr. Zachariah Miller, Montana State University

Comments

Post a Comment